cases

cases

cases

cases

cases

Reviewing the challenges and opportunities facing the creative sector

Reviewing the challenges and opportunities facing the creative sector

reviewing the challenges and opportunities facing the creative sectors

In 2019, dandolo was engaged by a state government body to undertake two different projects looking into the challenges and opportunities for the state’s creative sector. Specifically, the first project involved working with the state’s publicly owned cultural institutions to develop a collaborative framework with government to address future challenges. The second project evaluated the state body’s multi-year funding arrangements to explore any changes that could better support the non-government small, medium and independent creative sector. One of our consulting analysts, Bokyong Mun interviewed Rachel Melrose one of our Associate Directors and Bronte Adams, our Director, about their work on both projects.

BM: Can you tell us a little bit more about the two projects and what they were about?

RM: For the first creative institutions project dandolo supported the Minister’s Expert Panel to consider the strategic and operational opportunities facing the state’s key cultural institutions. The project aimed to identify a set of shared objectives and framework of expectations for government and the cultural institutions to enable them to collectively respond to future opportunities and challenges.

In the second creative sector funding project, we were engaged to review and explore any changes that the government could make to its multi-year funding approaches to better support the sustainability of the sector, comprised of small, medium and independent organisations. The project focused on a program that supported not-for-profit organisations through long-term operational funding.

BA: At the core, both projects looked into ways for government and stakeholders to better support and facilitate a stronger, more resilient and more sustainable creative sector. The creative sector is an area that dandolo greatly cares about, and our experience meant that we were well set up for both projects. For example we have previously done work on measuring the impact and value of the creative sector, developing strategies to increase patronage and yield for cultural and heritage institutions and on opportunities for the digital creative sector.

BM: Sounds like the projects were different but similar at the same time! Were there any challenges that were common to both projects?

BA: The two projects involved both the biggest and most powerful, alongside the smallest stakeholders in the creative sector, and with that kind of power imbalance it was important to carefully and transparently manage their interests and expectations. While the large creative institutions are publicly owned and of significant importance to the state, most of the smaller stakeholders were not-for-profit organisations looking to serve community needs. In addition, funding for the sector is always constrained, and stakeholders are sensitive to changes they perceive might leave them worse off. We looked to maximise the political, government and sector interests across both projects.

BM: What were some of the key conclusions / recommendations that we made?

BA: Across both projects, we considered the fundamental role of government in managing and investing in the key cultural institutions of the state. While the institutions individually are high performing, we found that opportunities were being `left on the table’ and much more could be done to collaborate and align on a shared strategy between the sector and with government. Ideas like sharing demographic data, linked digital platforms and a sector wide brand had the potential to add value, especially in building stronger ties with the small / medium organisations of the sector.

RM: For the stakeholders in the creative funding project, the operational funding they receive is key to ensuring that a diverse range of creative organisations and opportunities continue to exist. Our recommendations focused on how the government could better support a systematically underfunded cohort of the sector. We found four key ways that the operational funding program could be improved and better tailored towards the policy objectives it was supporting. This included considering differing performance and reporting expectations and the financial risk to government associated with the investment.

BM: What were some of your highlights from working on the projects?

RM: While dandolo has done a lot of work in the creative sector, personally I wasn’t very familiar creative sector before, and so it was rewarding to work on these projects. It was both challenging and interesting to explore and articulate the value of the creative and cultural sector. This was something we particularly got to explore when looking into the role that creative sector can play in promoting social, economic and cultural outcomes.

A big highlight from the creative institutions project was also the opportunity to engage and work with senior stakeholders across the key institutions through interviews and workshops. Having all of these people in a room is not something that happens often, and it was valuable not only for us, but for the stakeholders to discuss sector-wide issues.

BA: Personally I always enjoy the opportunity to work in the creative sector – it is an area that I think is inherently valuable to our community, even if not easily quantified and measured. The work that we did in the cultural institutions project has also been picked up by the Minister who is seeking to use the COVID-19 pandemic as an opportunity to implement our recommendations to support the sector through these difficult times. It is always amazing to see how our work can continue to have impact in unexpected ways.

BM: What do you think makes these projects iconic for dandolo?

RM: At a high level, the two projects were a unique opportunity for us to consider and show the value of the creative sector, and the role that it plays in the economy and the wider State. The creative sector is one that has been facing some really significant challenges, so I felt that our work had a lot of value in highlighting opportunities to maximise public value within a constrained funding environment.

BA: Both projects also highlighted the importance of starting form a clear conceptual framework. Having this helps to ensure that our problem solving is as comprehensive as it can be and provides a common language to talk about the project with the client and stakeholders. Most of all, I would say they are iconic to dandolo as high impact, challenging and successful projects. Our previous experience means that we know a lot of the stakeholders well. This allows us to act in a neutral but sympathetic way as we try to help the stakeholders in a traditionally underfunded and challenging sector.

review for a state education department of career education in schools

review for a state education department of career education in schools

review for a state education department of career education in schools

In 2017, dandolo reviewed career education delivered in government schools for a state education department. dandolo director Joe Connell (JC) and Senior Consultant Jade Peters (JP) worked on the job. They sat down with Michelle Stratemeyer (MS) to talk about it.

MS: Perhaps we can start with an overview of the project?

JP: Sure. The project originated from a meeting between a group of students and the State Minister for Education. The group represented students from regional and rural areas. They raised a range of concerns about public education, one of which was the topic of career education and counselling, which they felt was inadequate in its current form.

The Minister took a personal interest in the issue of careers education. To follow up, the Department commissioned an independent review of the current offerings in order to improve service delivery. dandolo submitted a proposal, with the support of some expert advisors, and we were successful.

MS: How did dandolo approach the brief?

JP: An initial challenge was how to scope the work. There was a real issue to deal with because career education can be defined really broadly. In some senses all education contributes to a student’s progression towards a career. But the intent of this project was to be narrower. So we narrowed our definition to formal career education structures and processes.

After we narrowed down to our scope, we reviewed the existing literature on what best practices in career education should incorporate. We then used this as our framework to determine the gap between the current offerings and the ‘gold standard’ ideal version of career education.

JC: For a review project like this we are always looking for a set of reference points against which to judge the status quo. In some projects that is a set of predetermined client objectives, or a set of criteria. In this project best practice played that role. Using this framework also allowed us to choose best practice that reflected the best and most up to date understanding about what works in career education. That was critical, because it helped us show that career education hadn’t changed in schools, even when the world around those schools was changing.

MS: With your framework established, what did you do next?

JP: We did a highly intensive, consuming program of fieldwork. Stakeholders included government, career educators, agencies, and students. We ran several focus groups with students to canvas their views on what the current approach to career education lacked, and how it could be improved. Students brought up the prospect that many traditional occupations would rapidly be automated, moved offshore, or evolve beyond the skills being taught in schools. They also thought careers were no longer likely to be linear and are now characterised by varying forms of employment. These types of comments showed that students were aware of the rapidly evolving work context that serves as a backdrop to career education in this era.

Our consultations also included engagement with those responsible for delivering career education in schools. For example, our team attended a career education conference, which allowed us an opportunity to talk with experts in the field. This gave us a sense of the divergence between those delivering career education, compared to the students receiving it.

JC: The engagement with young people directly was a really important part of the project, and Jade and I had a lot of fun facilitating focus groups with year 10s. Even though education is unambiguously for young people, it’s surprisingly rare how often they are consulted about its delivering. We’re doing more and more to incorporate a genuine ‘student voice’ into the education work that we do.

JP: Yes, and the students were really honest and insightful. The focus groups also yielded some of my favourite verbatim quotes like “careers classes are a bludge”.

JC: Not being from Australia that was a new term for me to learn and Jade had to tell me what it meant. But then I was determined to use it in the report.

MS: So, how did the status quo stack up against best practice?

JC: Like lots of things in a devolved schooling system the most honest answer is probably: it varies. We found some schools who were doing great things. They were employing high quality staff and running great programs. In others, career education was an afterthought, or a compliance exercise.

JP: Right, and even in schools that were doing well, their model of career education was probably struggling to keep up with the realities of the modern world. A lot of career education is focused on narrowing choices. Choose your Year 11 subjects, select your university course, and push for an ATAR. These days, with careers less defined, and the shape of the economy we will all work in less certain, we need to be focusing on a broad skillset, not a narrow one.

JC: There were other things too. Career education typically starts to late, is often uninspiring – or a bludge – in the eyes of students and isn’t experiential enough. And, when I say the answer is “it varies”, the schools that are least equipped were really not providing students with much at all.

MS: What did you recommend as a result?

JC: We had a suite of recommendations. Some of them were about reframing existing provision. To encourage career action plans to be of higher quality, we suggested schools be required to send them home alongside school reports. And we proposed standards for qualifications of career counsellors.

JP: Probably our most transformational recommendation was to have formal career education start earlier – year 9 or 10, say – and be more exploratory. About what students want and care about, and what they’re good at. That way, the intention is that by the time the come to make the ‘narrowing’ choices like what subject to take, or whether to stay in school, they have a better sense of possibilities.

MS: What came out of your recommendations?

JC: Our report fed directly into the Department’s budget process. Virtually all of our recommendations were picked up in a $109m budget bid. That included reprioritisation of existing spend, but new services too, especially for younger students.

JP: It was very satisfying to see the tangible impact that our work had. The changes are still be rolled out. We will be very interested to see whether they have their desired impact.

JC: On the one hand $109m is a lot of money. On the other, it doesn’t take that many young people being pointed in the right career direction, rather than the wrong one, or staying for an extra year or two at school, or transitioning into training well, to have that investment pay dividends.

MS: Finally, what do you think makes this an example of an iconic dandolo project?

JP: I really appreciated that we could bring the student voice to the foreground. Often, this is the perspective that goes missing, so we wanted to make sure they were heard. Interestingly, it was the student voice that was most aligned with the best practice guidelines that we identified from the academic and industry literature. For example, students had views on how to modernise and improve career planning for the current employment context that were very similar to expert views. In contrast, we saw more conservative, traditional thinking from decision-makers and practitioners.

Second, this was a project that really cemented our approach to focus groups. It was an opportunity to refine and test our engagement strategy, and given how clearly the student voice came through, was a success. I think both of these elements make this an iconic example of our work.

JC: And this is a project where we can draw a direct line between our work and a major policy and spending initiative that will touch every young person that attends a government school. Being able to say that is a huge privilege and I look back with real pride on the work we did here.

Review of Professional and Leadership Development in a State Education Department

Review of Professional and Leadership Development in a State Education Department

review of professional and leadership development in a state education department

In 2016/17 dandolo reviewed Professional and Leadership Development (PLD) in a state education department. Portia Waller (PW) interviewed on of our directors Joe Connell (JC) about his experience on the project.

PW: First of all, can you provide a quick summary of what this project was all about?

JC: A state education department commissioned dandolo to conduct an evaluation of their Professional and Leadership Development, as something that contributes significantly to education system improvement. dandolo set out to solve how this state department could lift their state’s education system through the delivery of a world class PLD approach.

PW: Did you think this work would be important? If so, why?

JC: The evidence is really clear that the biggest in-school factor impacting student outcomes is teacher quality. We also know that teacher quality is really variable. In fact, you typically see more variation between classes in a school than you do between schools, so the problem that you need to solve is at a teacher level, rather than a school level. In terms of the levers that an education department has to influence student outcomes, Professional and Leadership Development is a really significant one. To have the opportunity to do a top to bottom review of PLD in a particular jurisdiction was a really exciting opportunity to create significant change.

PW: The framework that you used for this project broke down Professional Development by function and career stage. What informed this framework?

JC: It’s a classic dandolo conceptual framework story; we break the problem down in a way that makes it easier to understand and helps us to identify priority focus areas.

In this case we broke first broke PLD down by career stage. We used the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers for this. There’s no need to create something new when someone else – in this case AITSL – has done the hard work, and especially when the framework is so widely accepted.

Then we broke PLD down into two different functions. One was the “business as usual training” that a system is always going to need. Like supporting new graduates to transition into teaching roles, or preparing new principals. Then, what became apparent in the jurisdiction in which we were working, is that PLD has another equally important role, which is to create specific system changes. For example, PLD can be used to drive changes in the way that we look at student behaviour or teaching literacy. We reflected these two very different purposes that PLD can serve in the framework.

PW: What were some challenges you faced with this project?

JC: In some ways there was a mismatch between the scope of the project and what was really needed. One thing we know about best practice Professional Development is that most of it should be informal, unstructured and on the job. People say that about 70% of PLD should be created by informal school culture, another 20% should be in-school but formalised, and then 10% should be formalised and external. So one of the acknowledged limitations of the job was that we were focusing on something that should in theory only be 10% of PLD. But at the same time, this is the bit of PLD that’s easiest for essential department to influence, so it makes sense to focus on it.

The other thing that was really tricky for the project methodology was that delivery of Professional Development was done all over the department; there was no single source of responsibility or truth. Every part of the department we talked to was doing bits and pieces of PLD off the side of their desk, so every time we talked to someone new we would get a lot of additional information about what was happening with PLD. This informed what we ended up saying, which was that the gaps in PLD and the variability in quality are really problematic, but that these issues are symptoms of the problem rather than the diagnosis. Our diagnosis was essentially that the organisation didn’t have an effective model that could establish what Professional Development they needed and ensure a high quality of delivery.

This is a challenge we’ve seen before in education departments. Because everyone is in the business of education and learning, everyone thinks that they can run some PLD ‘off the side of their desk’. This commitment to teaching others is really healthy. But the truth is that designing and delivering PLD are distinctive and specialised skill sets.

Making this diagnosis setup for recommendations that were structural, about how PLD should be designed, and organised, as much as they were about what gaps needed filling.

PW: What was different about working for this client?

JC: This was the first piece of work we did in this particular jurisdiction. I think it was the third education department I’d worked for at the time. That total is now up to five.

Working in a new jurisdiction meant that we had to be really sensitive to context and ask a lot of questions to understand the local environment. But it’s also true that you see analogies between different jurisdictions very quickly. You start to see patterns, and there’s a valuable process where you can compare and contrast different jurisdictions. There’s never a scenario where we’ll pick up a model from one jurisdiction and say it should be applied to another. But it’s really valuable to be able to draw a little from over here and a little from there and put them together and apply them. That was something we were able to really usefully do in this project.

PW: What were you proudest of in this project?

JC: Because of way we approached the project, and because our framework cut their Professional Development in a different way, we were able to tell the client a lot of things about their organisation and their practice that they didn’t already know, and quickly. For example, we identified hundreds of PLD offerings that the department didn’t have a core view of. Sometimes giving a client a new evidence base to work from is really helpful. I was also proud that we delivered some hard truths and supported the department to make some genuine trade-offs. Any time you reorganise your organisation it’s a really hard process; choosing to do something like end funding for a scholarship program and reorient that funding somewhere else is really difficult. Often times the hardest thing to do in government is to stop something that you’re already doing, and to acknowledge that there are better things to be doing instead. That can be a hard message to deliver, but if you do it well and do it in a supportive way then it can set your client up to do some really challenging stuff.

PW: How did the client respond to these “hard truths”?

JC: They responded really well. There was almost a bit of a sense of relief; there were some people in the department that had had some hunches, but they hadn’t been able to say them out loud because they didn’t have the evidence base to do it. The other thing was that everyone agreed with the objectives we had, and was on board with the idea that we should make the most of PLD. This meant that the whole organisation embraced our findings. Even though there were some difficult changes, everyone agreed that we were moving towards a really valuable end goal.

PW: What do you think was the major impact of this project?

JC: The single biggest thing was the department set up a new professional learning academy for teachers, which was a really big deal. It’s a standalone academy that works exactly as our advice said it should. We’ve subsequently also had the privilege of working with the department on the business plan for the academy, and it’s now in place and running courses. More generally, I think our work has led to a more disciplined and strategic approach within the department towards Professional Development. There has been a real reorientation of the support that’s provided to emerging leaders and new principles in the system.

Positive partnerships evaluation

Positive partnerships evaluation

positive partnerships evaluation

Positive Partnerships is a Federal Government initiative supporting school-aged children with autism and those who care for them. Since its inception in 2007, the Federal Government has invested more than $63 million into the program.

dandolo was engaged by the Australian Department of Education and Training in the first half of 2019 to evaluate Phase 3 of the Positive Partnerships program, which was delivered by Autism Spectrum Australia (‘Aspect’).

Laura Williams interviewed Dr Michaella Richards to learn more.

LW: Positive Partnerships had been operating for 12 years before we were contracted to conduct an evaluation. Can you give me some context for the project and an overview of our role in it?

MR: In Australia, about 1 in every 70 people has autism. The needs of individuals on the autism spectrum are highly complex and individualised, and students with autism are four-times more likely than their peers to require additional learning and social support services.

Positive Partnerships grew out of the ‘Helping Children with Autism’ funding package and is focused on strengthening the relationship between schools and families to improve the educational outcomes of school-aged students on the autism spectrum. This is achieved through a suite of face-to-face and online programs with parents, carers and school staff.

The program is well-established and -resourced; a rare Federal Government intervention into the primary and secondary education sectors. Given that autism afflicts all communities equally, it’s a universally popular initiative.

There have been three distinct phases during the project’s 12 years of operations:

Phase 1, which ran from 2008-12, was weighted more heavily towards providing professional development opportunities for school staff.

Phase 2, 2012-15, involved more programming targeted at parents and carers.

Phase 3, 2015-19, saw a reduction in professional development expectations for teachers and the introduction of training combining the cohorts.

Both Phase 1 and Phase 2 were evaluated by separate parties.

We came in at the end of Phase 3 to:

Ensure that funding had been used efficiently, effectively and economically; and

Inform decisions about the scope and development of a potential fourth phase of the Positive Partnerships Program.

LW: How did stepping in to evaluate a program that had already been reviewed twice impact your approach?

MR: It had quite an impact on our methodology. We didn’t want to reinvent the wheel or over-consult by repeating work that had already been conducted, and we were conscious that there was a lot of existing information spread between the previous evaluations, our client and the project delivery partner. We focused much more on synthesising information and analysing gaps.

We split our fieldwork in to two stages that broadly aligned with the elements of our brief. The first focused on evaluating the program’s performance to date; the second focused on the future directions the program should take.

In the first stage, we pulled together the disparate pieces of information and engaged with experts to develop a best practice framework against which we could evaluate Positive Partnerships. We were able to show that:

There was ongoing unmet demand for an intervention to support educational outcomes for students with autism;

Focusing on home-school partnerships was an effective way to do this;

The program resources were respected and useful;

The program was broadly delivered in-line with best practice principles.

In the second stage, we considered how Positive Partnerships should evolve in response to major changes to the operating environment for autism support. This involved using a ‘first principles’ approach to revisit fundamental questions around the program’s value, target market, solutions and delivery.

Using our gap analysis from Stage 1, we were also able to engage subsets of the population that hadn’t been included in previous rounds of consultation. This was important, as it meant we were able to make observations based on a more representation sample of people involved with the program’s entire life cycle.

LW: What were some of the key take-aways from this process?

MR: The main value was in identifying the “secret sauce” that made Positive Partnerships an effective program and making recommendations to tighten the program’s focus on the areas in which it could make the most difference.

Positive Partnerships had been conceived at a time when there weren’t many other service providers working on improving educational outcomes for children with autism. Over the course of a decade, however, this landscape had become more crowded and we were starting to see some duplication of efforts.

As a well-regarded, established program, it was also difficult to pinpoint the elements of the program that contributed to its success. Were all the program’s elements critical, or could its efficacy be attributed to a fraction of its operations?

We provided a robust set of recommendations to the Department that clearly spelt out:

drivers of Positive Partnership’s impact;

areas it should focus on to ensure effective service delivery;

more specific definition of the target market;

refinements to the suite of products offered;

ways to leverage existing government infrastructure;

potential to apply the program to other disability areas.

LW: Why was this project iconic for dandolo?

MR: I think that comes down to the scale, visibility and force of emotion around Positive Partnerships.

This was a very popular, very well-funded project. Stakeholders felt very passionately in support of it and there was a lot of anecdotal belief that the program was performing well.

In a public program of this size, however, it’s really important to be able to justify the use of resources. We approached the evaluation from the perspective of our client and the taxpayer to ensure that public funds were used to best effect.

We were able to use a robust evaluation to cut through that and assess if it was still having the intended impact ten years on. What was providing real value, what should we keep doing and what should we stop doing.

Startup mapping over the years

Startup mapping over the years

startup mapping over the years

In 2017, 2018 and 2020, dandolo was commissioned by LaunchVic to develop the Victorian Startup Ecosystem Mapping Reports. One of our consulting analysts, Bokyong Mun interviewed Lotti O’Dea, who was the project manager for the 2020 mapping report about some of her highlights.

BM: Can you give us a little bit of context behind what these reports were about?

LO: The Victorian Startup Ecosystem Mapping Reports provided a comprehensive and up-to-date view of Victoria’s Startup Ecosystem. Each report we updated and explored the different elements and strengths of the ecosystem as well as changes over time.

Startups are organisations with the potential to change the way we live and work for the better. They are able to quickly adapt and adopt new approaches to solve problems where a solution might not be obvious. While they often centre around technology, startups are not only technology-based and can be found across almost all sectors.

Developing these reports is particularly valuable for the startup ecosystem, as stakeholders such as policy makers and investors, need regular insights to inform decisions as well as celebrating achievements of the sector.

BM: What exactly does a startup look like? When you gathered your baseline data, how did you calculate the number of startups in Victoria’s ecosystem?

LO: While there is a lot of interest in startups globally, there actually isn’t one agreed approach to what a startup is, and the method that should be used to calculate the number of startups in an ecosystem. One reason why there isn’t a total consensus is because not all startups look the same, or share the same characteristics. For example, not all startups are registered businesses.

In our most recent report, we used a number of objective and subjective criteria to define a startup. These criteria were commonly used in internationally recognised definitions and surveys. Objectively, we looked for startups that were headquartered in Victoria, were less than 10 years old, and were active at time. Subjectively, eligible startups also needed to be innovative / disruptive, and be using technology to scale up.

On this basis we trialled multiple methods to estimate the number of startups in Victoria, so we could triangulate these estimates to a give us a credible figure. Our most conservative method was to count only those firms that we could identify as startups in the datasets we were using. We estimated a number more than twice that figure, by applied the rate of growth of new firms to the number of startups that had been identified in previous years. Trialling these different measures allowed us to work towards a robust figure, while recognising the conflict that exists on defining and estimating the number of startups.

BM: That is very interesting! Did these differences impact how you were able to gather your data for the report?

LO: We definitely had to be creative in how we gathered our data, but this was primarily because startups are known for being over surveyed. There are a lot of stakeholders such as government and venture capitalists who are very interested in startups. Our challenge was to figure out a way of collecting comprehensive data without putting too much burden on what are often, young and very busy organisations who may not see the immediate benefit of sharing data.

For our 2020 report, our base data was gathered through the Startup Genome Global Ecosystem survey. We supplemented this with a range of secondary sources and analysis such as data on key metrics that had been previously collected, and desktop research through sources like Crunchbase.

BM: Was there a part of the analysis that you have really enjoyed or were surprised by?

LO: Something I’ve really enjoyed is grappling with the conceptual and methodological complexities that sit behind what seems like a simple descriptive project, for example identifying the number of startups. I also enjoyed doing additional exploratory analysis on high growth startups in the 2018 report. In this analysis we looked to see if there were any particular patterns and features of these high growth firms. We found that on average high growth firms: are older, are more likely to have diversity and inclusion policies, have a higher proportion of firms using disruptive technologies and have founders that are older, have more a lot more sector experience and have founded more startups previously.

It’s also been rewarding to see how the ecosystem has changed and matured over the years. I feel a little bit like a parent, and watching the startup ecosystem grow and go out into the big wide world.

BM: What were some of the more conceptual and methodological challenges that you mentioned above?

LO: I think a clear example is illustrated by the fact that in the startup ecosystem, there is no “average” case, more so than in other sectors. Startups vary considerably, and there are outliers on all spectrums. The challenge is being able to summarise the ecosystem while still being accurate to individual cases.

Another particular challenge for the startup ecosystem is that the sector can often move really quickly. We have to take this into consideration when doing our analysis to ensure it is still up to date and be careful about any trends or comparisons that may no longer be relevant. The impact of COVID-19 on the startup ecosystem is a good example of this.

BM: What about these reports do you think makes it iconic to dandolo?

LO: I think at dandolo we’re proud of the way that we are able to communicate complex things in a simple way – and that is something we definitely do in these startup mapping reports. The startup ecosystem is complex and nuanced, and we’ve been able to bring some really valuable insights to a project that might just seem like straightforward descriptive analysis. Finally, at dandolo we love introducing our team and our clients to the joys of data and quantitative analysis – these reports have been the perfect project for our consultants to get deep into large datasets and pull out the insights that really matter.

Evaluation of a notebook program for teachers and principals

Evaluation of a notebook program for teachers and principals

evaluation of a notebook program for teachers and principals

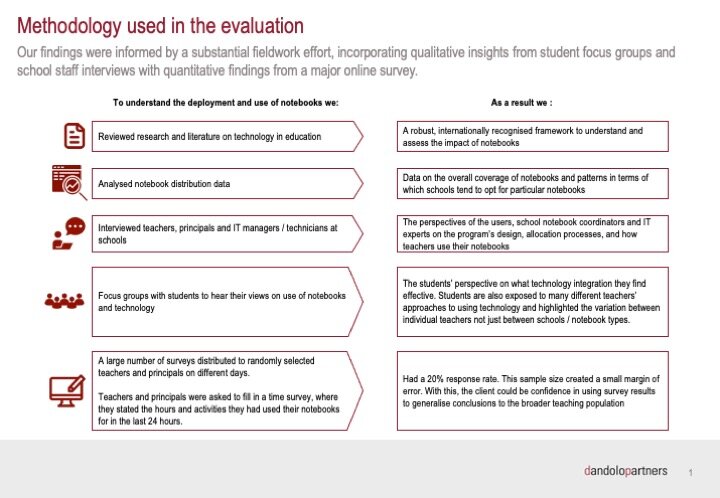

In 2018 / 2019 dandolo evaluated a state education department program which provided teachers and principals in government schools with access to notebook computers. One of our consulting analysts, Bokyong Mun interviewed Lotti O’Dea, who was the project manager for the evaluation about some of her highlights.

BM: Can you please give us a quick summary of what the project was about?

LO: dandolo was asked to evaluate a program that provided notebooks to teachers and principals in schools. The program aimed to equip teachers to better plan and teach as well as efficiently complete administrative work. The department wanted us to evaluate the design, implementation and impact of the program, particularly to see if providing the laptops to teachers were having beneficial flow on effects to students as well.

BM: Sounds like a big job! How did you approach the project / what was the team’s methodology going in?

LO: We focused on being comprehensive, particularly with our fieldwork. We carried out interviews, held focus groups at schools. We gathered an unprecedentedly large and rich collection of data about notebook use in schools, and we completed a major survey that was sent to 100 teachers on 100 random days during the year, so 10,000 in total. The survey asked about notebook use in the last 24 hours.

Undertaking all of the fieldwork was hugely valuable in how we understood and built frameworks to analyse our results. Specifically it helped us to understand how teachers in the program were using their laptops. Initially, we thought that any differences in how teachers used them would be linked to characteristics like the type of school, or social economic status and that this would be borne out in our survey data.

But from talking to teachers and students, we found that even in schools teachers were using the laptops quite differently. Our analysis of information we gathered from the surveys reflected this too, and we weren’t able to find a clear trend between how many hours teachers used their notebooks and the socioeconomic status of their school. We used this feedback to instead develop more nuanced profiles of the different user groups of teachers.

Developing these user profiles also provided a framework for outlining any future barriers that may be faced in promoting greater engagement with the program.

BM: What were some of the key conclusions that the team found?

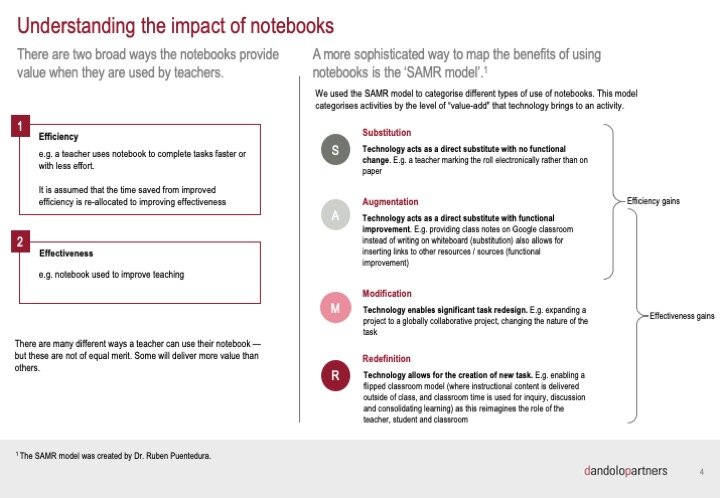

LO: Unsurprisingly, we found that notebooks were indispensable to teachers, and were being used for significant amounts of time. To figure out how the notebooks were beneficial to teaching and student outcomes, we used the SAMR model to map out the different ways that teachers used their notebooks.1 Using the SAMR model meant we were then able to analyse and capture the specific ways that notebooks add value to how teachers go about their roles.

[slide 4]In terms of improving teaching, the notebooks were most consistently being used to improve efficiency for things like teaching and lesson planning, or communication and administrative tasks.

But we found that around half of teachers didn’t use their notebooks for modification and redefinition activities – or uses that made their teaching more effective, and this was a big area in which we could provide recommendations to the department. Examples of some of these activities we did see included teachers personalising or customising learning to the student, or receiving real-time feedback from students on their engagement and understanding of the lesson.

Building these frameworks also helped us to communicate and illustrate our findings to the department.

BM: What was something in particular that you liked or are proud of about this project?

LO: I found the project interesting because we were able to provide really clear insights into an area where the department had very little visibility before.

An extra aspect of this project that was really valuable, was that the large number of surveys we sent allowed us to do some AB testing on the most effective way of sending out surveys. For example we found there was a higher response rate when we sent surveys out later in the day and where the subject line of the email sounded more urgent. On the other hand, factors like the day of the week, or the length of time between sending out reminders seemed to not to have any affect. These learnings have been really useful for other surveys that dandolo has done on other projects.

BM: What do you think makes this an iconic dandolo project?

LO: dandolo does a lot of work in the education space, and on face value this project can seem like just another evaluation of an education program. But looking beyond the covers we found the project was much more technology heavy and we ended up doing an evaluation that had a unique intersection of technology and education.

When we were working on the project, dandolo was also working on another evaluation project of the software program run in schools by the same state education department. This meant were able to provide joint analysis more broadly on the technology ecosystem in schools, based on our findings from both projects. Taking bits from both projects also allowed us to provide technological insights that were more fundamental and first-principles based, than we might have been able to otherwise.

1 The SAMR model was created by Dr. Ruben Puentedura.

Strategy and relationship building with medical research institutes

Strategy and relationship building with medical research institutes

strategy and relationship building with medical research institutes (MRIs)

dandolo partners have developed a unique concentration of expertise in consulting with medical research institutes around Australia. Senior Consultant Michelle Stratemeyer (MS) talked with Director Joe Connell (JC) to learn more about the range of work that dandolo has undertaken over the last five years in this unique sector.

MS: Joe, this interview is a bit different to some of the other ones we’ve done as we’re not talking about a specific project. Instead, we’re going to talk more broadly about the types of work we have done when working with a specific sector – medical research institutes (MRIs). Let’s start by talking about what MRIs are, and how they’re a unique type of organisation.

JC: Sure. MRIs are unique because of their strength of focus on research. Unlike universities they don’t do teaching and lecturing – although they do supervise some graduate students. They just do research. And while they frequently work very closely with hospitals and clinicians, they don’t have patients. The actual research they can do really varies. In Melbourne alone you have some MRIs with a ‘basic science’ research focus – upstream research about how our bodies and diseases in them work, you have others that incorporate a translational focus, and others still that work on public health or even social science research. But the unifying theme of all the MRIs is that strength of focus on research.

MRIs are a big part of the medical research ecosystem in Australia and Australia has a proud history of medical research innovations. The Cochlear implant is probably the iconic and historic example. But we’ve worked with MRI clients who are commercialising a new leukemia drug, and others who are manufacturing gene therapies to treat rare and horrible conditions in children.

Melbourne, in particular, has one of the best medical research output in the world, second only to Boston. And there’s a big collection of MRIs in Melbourne. But we’ve worked with significant MRIs interstate, too.

MS: Okay so they have a singular focus on research, what does that mean for the way that they operate?

JC: Well it certainly presents some challenges in terms of operations and funding. Universities get funded through student fees and government contributions for teaching students. It’s widely accepted that they cross subsidise research. Hospitals that do research are funded on an entirely different basis. But if all you do is research then all you can be funded to do is research.

Research grant funding has always been competitive, and that’s a good thing. But funding has gotten more competitive. For example, its more common now for projects to receive grants, compared to researchers receiving fellowship funding. As a result, there are instabilities in staffing. Coupled with this is an increasing appetite – particularly from government funders – for MRIs to be producing research that is translational and outcomes-focused. There’s new government funding – the MRFF – that will eventually match the size of the NHMRC funding, but is specifically targeted to translation. So, MRIs are needing to think much more strategically and commercially about the work they produce to meet these expectations.

On top of that, science is an inherently uncertain area to work in. Discoveries are made through investigation and testing, which means that it’s often people with a strong internal drive and curiosity who end up in this type of work. That can make it really hard for researchers to take a step back from the highly intense, specialised work they do to look at a broader picture where trade-offs between projects, areas and researchers have to be made for commercial viability. As outsiders, we often have a more objective view of which areas are strategically better placed for funding, but it’s also really hard for us to say which diseases or medical health issues deserve more attention. It can be a source of frustration for everyone involved!

MS: That gives a really good sense of the environment that MRIs work in, and some of the challenging aspects of their day-to-day operation. What sort of work has dandolo done with MRIs over the last few years?

JC: First off, let me say that our work is not about lobbying. What we are aiming to do is create strong, well argued, analytical strategies for the MRIs which we know will resonate and be understood by the intended audience, including government. Now, having made that point, I think you can consider our work as falling into one of two buckets. First, we have done a lot of work on strategic planning. Given the passionate, curious minds in medical research, this means having to bring people on board to take a hard look at the work being done and making decisions about what they will and won’t do in future. This is the basis of good strategy, but can be very hard to do. We encourage MRIs to develop strategy that focuses on priorities based on what is currently known, and to stay the course unless new evidence emerges which favours other priorities. Our value-add here is to clarify thinking: by identifying priorities we help MRIs to develop strong identities and distinguish the work they do from others in this space.

Our strategy guidance can also extend to helping MRIs work out how to present themselves to external parties. For example, MRIs tend to be relatively small compared to their typical partners in government, hospitals and universities. This can mean they have limited bargaining power by themselves. However, there is often value in collaborative relationships between MRIs to increase their clout. For example, we helped with a trio of medical research institutes that specialised in paediatrics. These MRIs had similar areas of expertise and focus, but were fragmented and working across multiple locations and facilities. They were also, at least indirectly, in competition with one another for funding (ARC, NHMRC, MRFF). By bringing them together, as well as creating cohesion with their associated universities and hospitals, we helped them develop a strategy for a funding pitch that they successfully made to government, resulting in ~$25 million in funding.

MS: And what’s the second type of work that we can help with?

JC: Second, we have had a number of projects that have been around understanding and strengthening MRI relationships with other organisations, typically either government or partner organisations such as universities or hospitals. One of the challenges of partnerships between different sectors or types of organisations is the lack of a shared language to communicate, or a shared sense of the value that MRIs produce with their work. So, some of our work in this space is just to develop an understanding of MRI value-adds, especially in economic, health and reputational terms.

This sense of value is then very useful in supporting MRIs for requests from government. For example, although MRIs attract a lot of funding via grants, fellowships and the like, these typically do not include indirect costs, such as those required for ensuring administrative and back-end support for the vital research work they undertake. Our approach was to take this evidence base around the value of MRIs, and use this to take an ‘upside’ approach to the benefits to the state, ensuring indirect funding was finally promised after 12 annual attempts.

But it’s not just about working on relationship building with government – it’s also important that the universities have strong relationships with their partner universities and hospitals. These relationships are symbiotic – both parties get something out of it. For example, universities benefit from the research output of MRIs, which contribute to their international rankings. MRIs benefit from getting access to research higher degree students and funding opportunities through partnerships with the universities. In helping to make that relationship flourish, we provide the MRIs with a strong evidence base for the dynamics of that relationship, which can inform the way they behave with their partners.

MS: We’ve talked about a lot of different kinds of work that dandolo has done with the MRI sector. In your opinion, what makes our work in this area iconic for us as a firm?

JC: First, I think we’ve managed to slowly but steadily build up a really diverse portfolio of work within this sector. It’s been great to really come to grips with lots of aspects of MRIs, including their relationships with other organisation and with government, and the role that they play in innovation. At this point, we can proudly state that we have dozens of MRI clients that we have worked with, and that these span multiple jurisdictions ranging from those with a single MRI to those with a thriving hub. It’s an unusual concentration of expertise to have built up and it is wholly unique to dandolo.

Second, I think that the work we’ve done in this space really speaks quite well to our capacity to have strategic cut through. We’re working with organisations that do incredibly important, impactful work but that sometimes lack the ability to communicate this in a way that connects and resonates, for example, with government. We’ve been able to take our knowledge and really use it to shape an approach to communication and strategy that has paid dividends for this sector. It’s been a very rewarding experience.

Finally, we’ve generated some really great outcomes. We’ve mentioned above the millions of dollars of well targeted funding that we’ve brought to MRIs from government. But we’ve also helped them make great decisions about things like where to invest in new technologies, or to expand or change their focus. In all of our work we like to see a path to impact, there is something special about knowing you’re helping to fund high quality research that can improve and save lives.

investment strategy for early childhood

investment strategy for early childhood

investment strategy for early childhood

In 2019, dandolo developed an investment strategy for a major philanthropic organisation to help them break cycles of disadvantage in Australia.

Disadvantage in early childhood can have a devastating impact on a person’s development, leading to life-long negative consequences for health, education and employment. This exposes future generations to disadvantage, which in turn perpetuates the cycle.

Senior consultant Tom Antoniazzi interviewed dandolo director Dr Bronte Adams AM and consultant Jade Peters about the project.

Bronte and Jade, in a nutshell, what did this project involve?

BA: This organisation had an overarching goal to break cycles of disadvantage in Australia. They knew they wanted an investment strategy focused on the development of children from conception to age four, but it was early days – they were still thinking about their priorities and were looking to move beyond talking about the problem, and there were high degrees of freedom to develop a response.

It was therefore particularly important to get clarity on problem definition and project logic: answer a number of key questions:

How do you define the problem?

What are the causal factors?

What are the options to address them?

What is the evidence for the highest impact approaches?

How do you filter down your options to a small number of smart investments?

We also encouraged them to think of their investments across the Foundation as a holistic portfolio with different risk profiles. They really liked this approach and used it to inform their investments overall, beyond early childhood education and care.

Why did this major philanthropic organisation engage dandolo?

BA: I think, as a baseline, dandolo has a reputation for bringing a lot of rigour to our thinking about each project. For this project, we were conscious of not standing back and admiring the problem which can be a trap for work around disadvantage. We wanted to deliver a rigorous framework and recommendations that would stand up to the strongest scrutiny.

We also appreciated how committed this organisation was to breaking cycles of disadvantage. We were able to take their mission on board to engage with the problem in ways that would help them achieve results within the organisation and beyond. This allowed us to ask critical questions about our own work along the way, such as “is it credible?”, “will it get through the Board?”, “will it convince stakeholders?” and “is it packaged in a way it will make a difference?”.

JP: The organisation knew we had extensive experience in the not-for-profit and early childhood sector and that we could help them develop a practical strategy to maximise the impact of their investments.

We also brought experience from a range of different policy areas and industries, which allowed us to think laterally about the complex problem of disadvantage and draw useful analogies (for example, taking the portfolio approach from finance).

Breaking cycles of disadvantage is one of the most ‘wicked’ problems in policy making. How did you handle the enormity of the problem for this project?

BA: I think the client valued the way we took a problem that was very messy and amorphous and reduced its complexity to lucidity and elegance. We did this using dandolo’s framework approach but also knowing when to accept ambiguity and move on from grappling intellectually with the problem. It’s OK to have false starts, but we find that you need to make breakthroughs early to avoid playing catch up for the remainder of the project.

To illustrate this approach, we had a few sessions to define ‘disadvantage’ where we looked at the characteristics of disadvantage and where they were most prominent. But we realised early on that categorising disadvantage by groups of people wasn’t going to solve the problem. We engaged early with practitioners around identifying potential approaches that would be more successful than previous efforts. In doing this, supplemented by our research and internal brainstorming, we identified that place-based solutions that simultaneously support people with different and complex needs were more likely to be successful than specific programs for specific people. This took us from problem definition to options for investment.

How did you approach the project?

I have talked about how we defined ‘disadvantage’ by looking at the literature and talking to experts.

The next question was how to prioritise potential investments to get the best return in terms of reducing cycles of disadvantage. We developed a number of criteria for investment based on the evidence, including ones focused on risk dimensions such as:

Short-term vs long-term investments

Low-risk investments in familiar areas vs high-risk investments in emerging areas with mixed evidence and high reward

Expanding existing initiatives that others are already working on vs trialling new initiatives

Using these criteria, we:

Shortlisted potential investments against the criteria. We picked out a handful of preferred options based on our appreciation of the organisation’s mission.

Thought about risk and implementation implications. This organisation was essentially a start-up and needed to get the strategy up quickly for a key board meeting at the beginning of the year.

What was dandolo’s impact?

JP: dandolo's value add was our ability to cut through the noise to develop an implementable investment strategy. The strategy clearly identified areas where they could play a distinct role to make a significant and long-lasting contribution to reducing disadvantage. This included:

Advocating for improved access to existing government services in maternal and child health for disadvantaged families

Supporting the early childhood and care sector to lift quality, particularly in low socio-economic areas

Leading, coordinating and evaluating the ‘place-based’ agenda

Expanding two existing early years programs

Supporting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander-led early learning services

Filling data and evidence gaps

We fundamentally changed the way this major philanthropic organisation thinks about maximising the impact of all investments, not just those in early childhood. Recently the organisation’s board approved a number of new investments across a range of policy areas, including early childhood, education and justice.

BA: It's a bit early to assess the strategy’s impact on breaking cycles of disadvantaged in Australia. However, as the organisation proceeds with implementation, we know they are taking a portfolio approach to make smart investments in things we know work but also higher-risk initiatives that may deliver breakthroughs. They are not making the same mistakes as other organisations, like duplicating government investment.

Why was this project iconic for dandolo?

BA: I think this project was iconic because you don’t often get the chance to work with an organisation with such huge scale and capacity and freedom to act. They were free from the constraints of government, which meant that they were more willing to engage with risk to discover more innovative ways of reducing disadvantage.

It was also iconic because we built a great relationship of trust, respect and enjoyment. We took on their mission and helped them to get their heads around the problem by reducing complexity and taking a structured approach to problem solving.

Developing a "campus precinct" strategy

Developing a "campus precinct" strategy

developing a “campus precinct” strategy

dandolo developed a “campus precinct” strategy in conjunction with a state government economic development department and a dual-sector university. Senior Consultant Michelle Stratemeyer (MS) talked with Michaella Richards (MR), dandolo’s Project Manager, for the job, to learn more:

MS: Let’s start by talking through the problem that needed to be solved.

MR: Primarily, this project was about economic growth for two different stakeholders with different needs: a state government economic development department, and a dual-sector university.

On one hand, the department had made a commitment to developing precincts, particularly for areas located outside the CBD and historically characterised by under development and disadvantage.

On the other hand, we were supporting the needs of our university partner. That particular university is basically the major university serving a large, very diverse and historically disadvantaged part of the city. The precinct strategy was an opportunity for the university to arrest declining student numbers by leveraging their significant precinct foothold in a way that delivered on the economic imperative for new industries and jobs growth in the region.

For the project, we needed to carefully balance the needs of both the Department and the university. For the Department, their primary concerns were with building local jobs and creating new and vibrant places in the State that would attract investment. For the university, with its strong mandate to service and support the communities in which it operates, it was important to have a strategic plan that recognised the needs of the local community as well as understanding how the precincts could contribute to the university’s ongoing and future success.

MS: And how did dandolo assist in solving this set of problems?

MR: we came on board to help with developing a strategic approach for the university related to their key precincts. This was two-pronged:

We assisted the university in developing an overall, comprehensive strategy for all their campus precincts that aligned with the precincts value creation framework for the state government;

We developed a unique strategy for each of the four campus precincts and how these related to each other and their local communities. These strategies captured what each campus would focus on, how they would provide services that were appropriate for the local community, and how their activities would integrate with industry needs. Each ensured that the relevant campus would sufficiently meet the demands of the precinct, as well as the university’s ambitions to provide high quality education to its community.

These strategies were integral for the university’s approach to investment and bidding for further funding.

MS: Other than successfully developing the strategies, what was the broader impact or outcome of our work?

MR: First, the strategic plans we developed were integral for the university to secure their own Board agreement on internal investment as well as in bidding for further funding from other partners including governments of all levels.

Second, on a broader level, our work was also important to underpin advocacy on key policy changes to support the university. The strategies we developed helped the university build a case to lobby on a number of fronts – for example, for more funded student places in key precincts or improved local transport infrastructure.

Finally, it is important to note that the project is ongoing; we are continuing our relationship with the university as we develop the strategy for the fourth and final campus. This campus was the most developed when we first began this work. We are continuing our work to create a robust strategy for this campus, which ties in the potential for infrastructure and employment opportunities in the precinct due to the presence of this campus.

MS: This project sounds like it was rewarding but also challenging. What did you find most difficult about it?

MR: It was rewarding, but difficult at times. One of the biggest difficulties was in guiding the university to set priority areas that were different for each campus precinct. Universities obviously have an important role in providing general education to students. However, the dual-sector nature of this university meant that there was also a strong imperative to determine specialisations that would best serve the students, communities and industries in the surrounding precinct.

We also saw some tensions arising between the overall precinct approach of the university, and the value of each individual campus. Part of our role was to create harmony between these priorities to ensure the project would be a success.

Finally, we also ran into process challenges, such as legal issues including land or title trades. We had to ensure we had a strong understanding of these areas so that we could develop an accurate value capture framework and that our work was not compromised by these challenges.

MS: Why do you think this is a good example of an iconic dandolo project?

MR: This was a really large, impactful project of considerable scale. I found it deeply gratifying to work on a project that was around developing and improving access to education in an area characterised by lower socioeconomic status, lower levels of education access and large populations of new migrants. Given the area has historically been underserviced by infrastructure and policy, it was great to be focused on the challenges of this set of precincts and developing an approach that could significantly improve them.

It was also a good demonstration of dandolo’s ability to work across a wide variety of objectives, including economic development, inclusive growth, working with diverse communities, education policy, and more. It was a complex, multifaceted project that required a team capable of managing that complexity while delivering a strong, successful outcome.

Finally, the project demonstrated our ability to manage the needs of multiple stakeholders in a way that satisfied them all. Our work was partly for a government audience that was focused on developing the precincts and needed a strategy that spoke to their policy needs. But we also balanced the needs of the university, which was grappling with declining revenue from decreases in student numbers. It was grappling with needing to meet the needs of the community, compete with other higher education providers, and deliver a commercially successful outcome. dandolo was well placed to manage these competing, sometimes contradictory, needs in a way that satisfied all parties.

Major Evaluation of Teach for Australia

Major Evaluation of Teach for Australia

major evaluation of teach for australia

From May 2016 to March 2017, dandolopartners was contracted to evaluate a major national education intervention focused on new education pathways for teachers. Laura Williams, dandolo’s Operations Manager, spoke about this project with Joe Connell. Joe is one of the firm’s directors and the project manager on this evaluation.

LW: Joe, thanks for speaking to me about this project. Before we launch into dandolo’s response, can you share some information on the project’s background?

Probably the first thing to understand is what Teach for Australia (TFA) is. It’s known as an alternative pathway into teaching. TFA:

Selects high achieving graduates with no prior teaching experience,

Provides them with intensive training and support, and

Matches them with disadvantaged secondary schools where they are paid to teach for a two-year placement.

It’s similar to Teach for America, or Teach First in the UK.

TFA was, and still is, substantially funded by the Australian Government education department. The department commissioned us to evaluate TFA. This meant we had to assess to what extent it was delivering on the department’s objectives for its investment, and whether there was scope for improvement.

Our evaluation took place around 2016, six years into TFA’s operations so the model was reasonably mature and TFA was operating at scale.

LW: I’ve heard it said around the office that this is one of dandolo’s most iconic projects. How did it get that reputation?

JC: Well, there are a couple of responses to that question. For me personally, this was a real coming of age project. It was the first project that I had worked on for a federal client and was also the most substantial in scale, nature and duration that I’d tackled. It was also, importantly, when I started to explore some of the analytical tools that have become integral to dandolo’s toolkit.

From the perspective of the firm, this project epitomises the kind of work we love. It’s aligned with our values, high-profile and challenging. It was an opportunity to deep-dive into a program that is exciting, and full of possibility, but that also had some serious critics, and has, at times, been controversial. And to cut through of all of that to understand whether and how TFA was delivering public value and how it could deliver more.

We’re also really proud of the quality of the advice that we provided, the change it precipitated and the lasting relationships we built with clients that remain well after the project formally concluded.

LW: What was noteworthy about the approach you took to this project?

JC: One of the things that sticks in my mind is how we incorporated ways of thinking from traditional evaluations and management consulting. We started by coming up with a framework to describe our client’s objectives and their key drivers. Then we developed hypotheses – with our client – about which drivers were the most significant, and which needed the most interrogation. That allowed us to be really efficient in targeting our analysis for maximum value.

In a project like this, that meant spending relatively little time confirming that high quality candidates were indeed attracted to the program and spending more time figuring out if graduates of the program stayed in teaching and teaching in disadvantaged schools.

LW: So what’s an example of an area where you really focussed your attention?

JC: As I said, the question of how long graduates of the TFA program stay teaching – rather than joining public policy consulting firms, for example – and whether they stay teaching in disadvantaged schools, was critical in the project. The client was basically investing in high quality teachers in lower socioeconomic schools. Each year a TFAer stayed in a school, they got a return on their investment. Whenever they moved on, they did not.

So we looked at the retention question in different ways.

We started with TFA alum survey data, which at the time had quite low response rates, and sough to triangulate.

One jurisdiction was able to run an analysis of their payroll data. Payroll is great because it’s granular, quite intimate, and very rarely wrong!

We were also able to ‘cyber stalk’ TFA alums. Stalk is not really the right term, because we relied on public information only, but we found LinkedIn, school newsletters and various other online mentions to be a rich source of information.

Through all this we developed a comprehensive and nuanced view of the retention question.

LW: What else did you do that was innovative in this project?

A couple of things come to mind.

As a nation-wide program that aimed to disperse its graduates, it would have been really hard to conduct a meaningful number of stakeholder interviews in person. Using online focus groups, we were able to involve a greater number of participants than we would have been able to meet face-to-face and we reached a broader, more representative cross-section of the cohort. Current and former TFAers were enthusiastic participants in this fieldwork. They logged in daily over the course of a week and engaged with our moderators, and each other, in a format that felt like a discussion forum. That was the first time we used this tool. We’ve done online discussion forums in a handful of projects since.

One of the most useful outputs of this project was a value-for-money analysis we conducted to quantify the benefit realised for the Department’s investments. This was important a) just because we were talking about a spend of public money for which TFA needed to be accountable but b) because it provided a useful frame to consider changes to the model. If we could lower costs, or increase the number of additional teaching years created, that would improve value for money.

LW: Finally, what impact did the report have?

JC: You can see a bit of the report for yourself. As is common on projects like this, we produced a public executive summary. That’s here.The report proved the extent to which the program was delivering on the Government’s objectives and the Department was able to use this evidence to retender for services. I think it helped the department reiterate their frame of reference for their investment.

In the short term they renegotiated their contract with TFA, and some of the recommendations we had made ended up as provisions. Then, in the medium term, and consistent with our advice, the department chose to go to market for suppliers of alternative pathways into teaching. TFA was successful in this process, but so was another program based out of La Trobe university. And my understanding is that the TFA contract after the competitive process further reflected some of the changes we had proposed.

Infrastructure funding

Infrastructure funding

infrastructure funding and financing

BC: Joe, in a nutshell, what did this project involve?

JC: We were commissioned to consider how infrastructure should be funded and financed. That’s a huge question. And that brief came about in a pretty interesting way.

A state planning minister commissioned an expert panel to look into a specific question about how particular aspects of residential and commercial development are financed. Think of, for example, the roads linking a new subdivision. Or more wastewater capacity to support infill housing. Who should pay for that? How much should they pay? And who should raise the capital needed for the infrastructure build?

The panel acknowledged that there were a number of issues with the status quo arrangements. Including that it has been built out over time, bit by bit. That often leads to some complicated and inconsistent arrangements. I guess part of the reason they commissioned us is because they wanted to be part of the solution to that, rather than reinforce the problem. They recognised that any recommendations needed to fit into a broader picture, of how government should arrange funding and financing for all infrastructure.

So, our task was to come up with a logical, defensible, first-principles framework for funding and financing all kinds of infrastructure, from the very small to the very large. I guess you could say we were their wide-angle lens.

BC: How did you start the project when the brief, and the question, was so large?

JC: Well, we looked at what other people had done in similar contexts, and we played with a bunch of different options that didn’t work. We thought about breaking it into different categories of infrastructure e.g. transport, utility etc. This didn’t work for us because, although they are both technically transport infrastructure, bike paths are very different to airports. We also tried to break it down into what form of government was responsible for that funding at the time. We found there was no logical breakdown of why these types of funding’s fell into different levels of government.

So we started to think about the underlying characteristics of different kinds of infrastructure that define them. We looked into the lifetime of the asset, the scale, level of cost etc. We had a breakthrough when we conceptualised the problem from a private vs public benefits perspective. This way of thinking led us to a very useful frame of reference by applying a market failure lens to work through the project because the underlying features of the infrastructure helped reveal the real problems we were trying to tackle through government involvement. Was this a matter of a natural monopoly? Maybe there were externalities, or public goods.

I’ll (reluctantly!) spare you the economics lesson. But we did find that applying some pretty simple economic ideas was a good starting point for a logical framework. That’s not to say we were completely bound by the market failure lens, though. For example, we also looked at situations where rather than responding to market failure, government might want to invest ahead of demand to stimulate new patterns of development. Like, say, a new highway or railway line that encourages population to grow in a particular way.

We also found that length of life of the asset was particularly influential in our thinking about financing. We preferred debt as a way to smooth costs over the lifetime of an asset.

BC: What made dandolo’s approach to this project unique?

JC: This project is the first of its kind that dandolo had tackled. So, we weren’t bringing existing views / sector expertise to the table. What we did bring was a really good first principals, problem solving skill set. What the client found refreshing was that our approach was genuinely from first principles. We were prepared to consider, and then discount, more conventional ways of thinking about infrastructure. Firms who are deep in the weeds on their thinking about infrastructure may have struggled to see the woods from the trees, whereas we were able to be clean and conceptual with fresh first principals thinking to the problem.

Additionally, at dandolo we don’t pretend to be specialists at everything, we’re prepared to bring people in from other contexts. I brought in a colleague from a former life consulting in New Zealand. We’d worked together on government financing for infrastructure, and he’d gone on to do wider infrastructure advice. We had always worked well together and it was great to reconnect. And then we also had Dan Norton who is a regular, and incredibly valued, dandolo project partner. Dan had recently come off the Board of Infrastructure Australia. His experience meant he gave great, insightful feedback. He always shares his considerable wisdom generously.

BC: What do you expect the broader impact of dandolo’s work on this to be?

JC: I know it was a very useful and important framing tool to help this expert panel. I know it confirmed some of their hypothesis and suspicions, but also provided them with challenge. And I know it gave them a sense of coherence and a strong frame in which to view their smaller scale recommendations.

I don’t think it was necessarily a direct line between our work and a change in government action. However, I think it did have an important framing impact and gave our clients confidence to make recommendations that were more significant / heroic than they would’ve done if they had just done the traditional, bottom-up stakeholder perspective.

BC: What about this project makes you proud?